Alongside the sheer audacity of the moment, came a celebration that thrust two fingers in the direction of a sensationalist-driven British press, during the summer of 1996.

Splashed all over the front pages for an exuberance and enthusiasm that was given the narrative of depravity, when handed a night off in Hong Kong by the England manager Terry Venables, prior to the 1996 European Championship, his players had emphatically let loose.

Stumbling into a notorious nightclub, within the spirit of an 18-30 bar crawl, it wasn’t long before Gascoigne and some of his teammates were in the Dentist Chair, head thrown back, while vast quantities of alcohol was poured directly into their mouths.

Nobody could suggest it was the ideal preparation for a major international tournament, yet these were predominantly Englishmen in their 20s, doing what Englishmen in their 20s do when they’re on holiday in warm climates.

The zenith of English football’s drinking culture, at a time when Liverpool’s talented collection of ‘Spice Boys’ had lost out in the FA Cup final to Alex Ferguson’s eminently more disciplined and focussed Manchester United, it was a time where any perceived lack of professionalism was becoming increasingly frowned upon.

Thirty years of hurt and all that, this was an era in which most of the nation seemed to be invested in the national team, in a way that simply isn’t replicated today.

Huge expectations had risen to the surface, with a tournament on home soil, and a post-Graham Taylor feel-good factor that was just six years beyond England coming within a penalty shootout of reaching the 1990 World Cup final.

Whenever England played in the finals of a major tournament at that time, the following day’s newspapers would be awash with images of empty high streets and sparsely populated motorways.

Non-football fans would be hooked, just as they would become tennis experts for Wimbledon fortnight, or be absorbed by any potential British success at the Olympics.

The England national team operated under the most intense microscope, and when, on the back of the events in Hong Kong, there was substantial damage done to entertainment equipment on their Cathay Pacific flight back to the UK, the scrutiny and rancour increased in volume.

By the time Venables’ side had laboured to a 1-1 draw in their opening game against Switzerland, a growing siege mentality had begun to kick in. In part, this had been engendered by the Football Association itself, when refusing to consider discussing a new contract with their manager until after the tournament.

With shades of Bobby Robson at Italia ’90, Venables had quite rightly felt slighted enough to declare he would not be continuing as England’s manager beyond the end of his current contract. The FA’s response was to name Glenn Hoddle as the new England manager elect.

It all added to a recipe that meant England’s squad at the 1996 European Championship became a closely knit one. It was very much a case of Venables and his team against the rest of the continent.

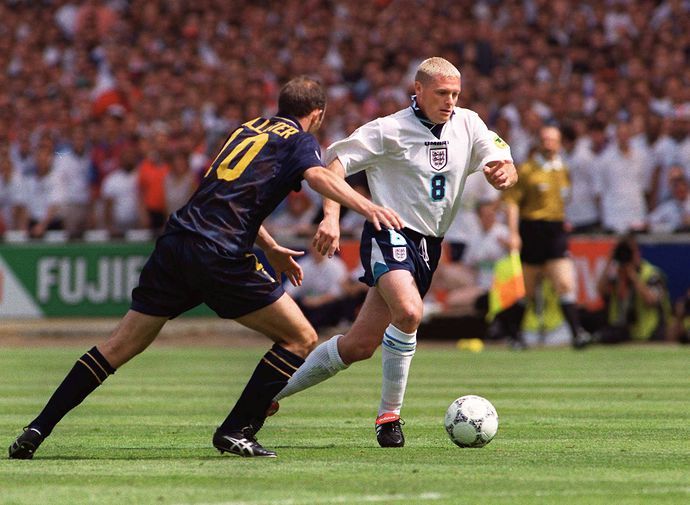

After an uninspiring first half against Scotland, in which Craig Brown’s side had shaded the better of play without being able to make a breakthrough, the complexion of England’s entire campaign pivoted towards a new direction during the second 45.

Having gone formation-for-formation in the first half, Venables jettisoned 4-4-2 in favour of 3-5-2: Jamie Redknapp replacing Stuart Pearce at the interval. It was a tactical alteration that gifted Gascoigne more freedom.

Within eight minutes of the restart England had the lead. Redknapp instigated the move, Steve McManaman was the facilitator, Gary Neville the deliverer of the cross, and Alan Shearer the goalscorer at the back post.

Scotland stung; David Seaman was forced into a fine save from a Gordon Durie header, while it was the same player who was the threat with 13 minutes remaining, when Tony Adams brought him down to gift a penalty.

A heavy sense of déjà vu from the Switzerland game seven days earlier, with the Netherlands still to be faced, England’s future in their own tournament would have been vulnerable had they conceded an equaliser at this point.

Up stepped Gary McAllister from 12 yards, out jutted Seaman’s elbow and the ball somehow ended up bouncing away for a corner. Incredulously, within 60 seconds, England were in possession of a two-goal lead, thanks to a piece of Gascoigne genius.

Latching on to a hopefully-looped pass forward, Gascoigne came face-to-face with Colin Hendry as he entered the Scotland penalty area. Taking the ball on his left foot, with a deft first-time touch, he sent it tantalisingly over the head of the Blackburn Rovers central defender, who was automatically wrong-footed and fell to the turf.

As the ball dropped, Gascoigne caught it perfectly on the volley, sending it low to Adam Goram’s right. Within seconds, the England number eight was on his back, simulating the Dentist Chair with his delirious teammates.

It was a moment of redemption for Gascoigne, not only for the pre-tournament rancour, but also for an international career that had failed to take wings in the manner expected of it, following his blossoming at Italia ’90.

Having missed the 1992 European Championship due to his own sense of misadventure at the 1991 FA Cup final — coupled with England’s failure to qualify for the 1994 World Cup — this was a Gascoigne with everything to prove, even more so after a fluctuating three years in Serie A with Lazio.

That Gascoigne had elected to regenerate his club career in Glasgow only added an extra layer to the events unfolding at Wembley.

What tends to fall into shade from this game, however, is that apart from Gascoigne’s goal, this was not a game that was embossed by his skill, in wider terms. It was instead notable for his determination, hard work, and most impressively of all, his discipline.